Mending fishing nets on top of the kiln in Porth Colmon

The west coast of Wales, its soils leached by heavy rainfall, needed an alkaline component such as lime to return the acidic earth to a neutral level to help plants and grass to grow. Treated lime is highly volatile and reacts with water so it was more practical to transport the blocks of limestone as a raw material and process it near to where it would be used. Roads were narrow, uneven and winding and transporting enough large blocks of stone by small cartloads would have been time consuming and awkward so ‘flat-bottomed’ boats were used to bring the stone by sea. Cargo would be landed onto the sandy beaches while the tide was in and the boats would be refilled with local farm produce taken on board for export. It was the most practical solution to build the kilns just above these beaches.

Landing limestone at Porth Sgaden

The benefits of lime have been known for thousands of years and there are records of lime kilns dating back to mediaeval times although then it was for use as a mortar, as a lime wash for buildings or as a disinfectant. Lime was (and still is) also used in the building trade as a component of mortar and as a wash to protect the outside of houses. In livestock farming, hydrated lime can be used as a disinfectant producing a dry and alkaline environment, which inhibits the growth of bacteria.

Construction

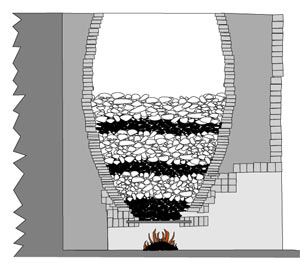

To produce lime in a form that would benefit the soil, stone or slate kilns were built near the beaches where the limestone was delivered. Lime kilns can be round or rectangular and built from local stone or brick. They were built with an outer shell and an inner burning ‘pot’ with an infill of rubble. The ‘pot’ of the stone kiln was lined with firebrick to prolong its life. The draw-hole at the base allowed air to flow into the chamber and keep the culm alight. The top of the chimney would be covered to control the burning rate. There was often more than one lime kiln at each site.

Lime burning

The stone would be loaded in at the top and layered alternately three or five parts limestone to one part culm (the burning fuel which was a mixture of anthracite dust, local clay and water). A fire was lit at the base of the kiln, the layers of culm would in turn start to burn and the limestone would be heated to temperatures of 900-1100°C. Carbon dioxide from the limestone and sulphur from the low grade coal dust combined to produce noxious gas and fumes that were emitted from the like kilns during the burning process. After 3-5 days the culm would have burnt away converting the limestone to quicklime. This would be left to cool, another four or five days, and the quicklime raked out of the kiln. Quicklime is extremely volatile and corrosive so farmers would leave it in heaps to absorb rainwater, which neutralised its corrosive effect, before spreading it on the land. This process is called ‘slaking’. The lime would be added to the soil in a ratio of 4 tons to the acre.

Industry decline

The industry started its slow decline as the railways came to the area in the 1860s. It was speedier to transport the limestone by rail to kilns that could be more strategically placed to service outside demand. Additionally other methods of re-energising the soil were being used, such as guano, the forerunner to other manures. The kilns along the shores of Wales fell into disuse and decayed under the assault of coastal weather so few now remain to remind us of that time. Today you can see the remains of lime kilns in Llyn at- Porth Colmon, Porth Sgadan, Porthor, Abersoch, Bwlch Bridyn (Morfa Nefyn), Wern (Nefyn) etc.

The draw-hole Porth Colmon kiln.