Llangwnnadl means the Church of St. Gwynhoedl. He is reputed to be one of the sons of the Welsh Chieftain called Seithenyn, who, in his folly, was responsible for the drowning of the fortress or township called Cantre’r Gwaelod, which is now submerged in Cardigan Bay. Like his brothers, he was a member of the College of Dunawd in Bangor Iscoed (Bangor on Dee) and one of his brothers called Arwystli Gloff settled as a recluse on Bardsey Island.

Tradition has it that the family came here from Llannor, a village near Pwllheli (indeed there is a place in Llannor called Maes-Gwyn), and that Gwynhoedl, their leader, died before they left. They brought his body for burial here.

The earliest settled communities on the Llŷn Peninsula from the fifth millennium BC were agriculturalists. Their lifestyle was sedentary, not nomadic, they herded and corralled livestock, they broke and turned the sod, sowed their seeds and harvested their crops in the autumn. Their religious, ceremonial and funerary monuments which have left such an evocative mark on the landscape would seem to be permeated with mysteries of the cycle of the seasons and a concern for the fertility of the soil. It remains, nevertheless, that the evidence of settlement and the agricultural impact on this Neolithic landscape is extremely scarce. The survival of megalithic chambered tombs or the tradition of their former presence may be an indication of areas of population density during this period but the evidence is so dispersed as to be of little account in this respect. There is a tomb at Cromlech Farm, Four Crosses; another at Pont Pensarn on the rising ground behind Pwllheli and another on the headland of Mynydd Tirycwmwd. There are two tombs on the Cilan peninsula, south of Llanengan and a further two tombs on the eastern flank of Mynydd Rhiw. All of these have been recorded on the east side of the peninsula, on ground which is to some degree elevated. Two tombs are recorded closer to the west coast near the headwaters of the Afon Soch. One, Tregarnedd, is now lost; the other, on the north flank of Mynydd Cefnamwlch, is a local landmark.

The distribution of surviving monuments of the Earlier Bronze Age, towards the end of the third millennium and the early second millennium BC, is similarly dispersed, though more numerous. The funerary monuments, represented by stone cairns, earthen barrows and ring ditches show some degree of concentration on the high ground of Yr Eifl, particularly their peaks and the adjacent mass of Carnguwch. To the south-west, there is a standing stone on the south-eastern flank of Moel Gwynus at 160 m OD and on the lower, moorish ground close to the headwaters of the Afon Erch and, further to the south-west, the Afon Rhyd-hir. There are standing stones across the river from the church at Carnguwch and two stones, 170 m apart at Tŷ Gwyn, to the north-east of the visible outcrop of Moel y Penmaen. There are standing stones near the Afon Erch between Pencaenewydd and Y Ffor. Another important concentration of cairns on Mynydd Rhiw is flanked by standing stones and a cist burial between Mynydd Rhiw and Mynydd y Graig and an urn burial on the northern slopes of Mynydd Rhiw.

There are standing stones at Llangwnnadl and Maen Hir, Pen y Groeslon and in the churchyard at Sarn Meyllteyrn. A cairn with urn burials has been recorded on the slopes of Foel Meyllteyrn and a cluster of seven ring ditches with central graves and ploughed-out barrows has been excavated at Bodnithoedd, at the western end of Botwnnog. These latter burials were discovered by the presence of their cropmark ditches and are an indication of a possible greater density of similar sites, erased form the landscape by later agricultural activity on lower ground.

Urn burials have been recorded, again on lower ground, at Pen yr Orsedd, Morfa Nefyn, and a possible round barrow nearby. A cluster of three barrows stand within 30 m of each other at 50 m OD, near the house of Cefn Mine, south of Bodfel.

A cairn and stone-lined cist stands on the plateau, at 340m OD, immediately below the summit of Carn Fadryn and a possible cairn stands below and to the south of the visibly striking cone of Garn Saethon at 165m OD.

Settlement enclosures with varying degrees of defence or fortification and enclosed or unenclosed hut circle settlements are more sure indicators of later prehistoric farms in the Llŷn landscape. Nevertheless, the distribution is weighted in favour of locations on marginal land and upland where the potential for the survival of evidence is greatest. In the dry summers of 1989, 1990 and 2006 several new enclosures were recorded as crop and parch marks with no other surviving remains above ground, the evidence having been erased by centuries of ploughing.

Few of these settlements have been excavated to any great degree and little evidence for the farming regime has been forthcoming. An important exception is the double-ditched concentric enclosure which stands on a slight promontory overlooking the Afon Soch at Sarn Meyllteyrn. The settlement spans the end of the second and early first millennia BC. Pollen evidence suggests an open grassland environment with wheat and barley cultivated in the near vicinity.

The greatest density of surviving small farms, of the later prehistoric and early Roman centuries, lie on the slopes of the granite masses which range from Yr Eifl in the north to Garn Boduan in the south-west. There are nucleated groups and single round huts on the seaward facing slopes of Gallt Bwlch and between Llithfaen and Pistyll. A dispersed scatter of single huts and a nucleated, enclosed group nearly, lie on south-east facing slopes below Bwlch Farm, in the same area at around 200 m OD. These settlements are at altitudes within cultivable limits but which are conveniently sited to access summer grazing on the higher ground.

There are fourteen settlements occupying the southern and south-eastern slopes, south of Llithfaen and Pistyll, in the general altitude range of about 150 m OD, more or less, following the contour from Moel Gwynus to Moel Tŷ Gwyn, Cerniog, Mynydd Nefyn and the lower slopes of Garn Boduan and looking out over the flat lands of Boduan and the Afon Rhyd-hir. Ten of these settlements are nucleated and enclosed and we can be certain that these represent established small farms of the later prehistoric and Romano-British period. These small farms are well-placed to exploit a cross-section of a diverse landscape which includes arable cultivation and stock rearing and in this context, the intractable higher slopes of the igneous intrusions should be considered a resource rather than a constraint.

There are two very substantial and broadly contemporary stone-walled fortifications in this area. At the northern end, Tre’r Ceiri occupies the easternmost peak of Yr Eifl at 480 m OD. At the southern end Garn Boduan rises above Nefyn and the coastal plain to 270 m OD. Both hillforts have extensive and strong defences and both display clear evidence of hut circle settlement within their ramparts. At Tre’r Ceiri a chronological sequence is identifiable in the replacement of large circular stone-walled houses with smaller, compartmentalised units. There is also evidence for the maintenance and repair of part of the rampart during the second century AD. An argument could be advanced that these forts, at altitude, could be related to stock control and summer pasturing, particularly so in respect of the potential hazard of cattle raiding in the summer months and the historically recorded use of these uplands for grazing in later centuries.

A comparable context might be met with in the area of Carn Fadryn, Carn Bach and Garn Saethon, at 370 m, 280 m and 220 m respectively. Carn Fadryn has an extensive plateau at 340 m, defended by stone ramparts. Single, dispersed hut circles occupy the lower slopes of Carn Fadryn and the saddle between it and Carn Bach. Another dispersed group occupies the south-eastern slopes of Carn Bach. Nucleated enclosed and unenclosed hut circles constitute farmsteads on the flatter land overlooking the west flank of the Nanhoron Gorge.

There are defended enclosures at the north end of Mynydd Rhiw, on a break of slope on the south east side of the hog back and, as the ground rises again, a third hillfort, Cregiau Gwineu, along a basalt intrusion at the summit of Mynydd y Graig. There are several circular settlement enclosures and nucleated hut circle groups on the south-western, and south-eastern, slopes above the saddle between the south end of Mynydd Rhiw and Mynydd y Graig and a string of single and dispersed hut circles on the steep south-eastern slopes of Mynydd y Graig, overlooking Porth Neigwl and Caridgan Bay. Mynydd Rhiw and Mynydd y Graig were areas of upland grazing in more recent centuries and it would not be unreasonable to suggest that the disposition of later prehistoric settlement valued that landscape for the same reason.

Castell Odo is a relatively small bivallate hillfort on a low, but nevertheless, locally prominent rounded hill, rising from the Aberdaron plateau at 146 m OD. The defences were remodelled and replaced several times. Its situation might suggest a main function as a focus of local or regional lordship and control. Nevertheless, notwithstanding politically strategic considerations, the fort is sited at the interface of the productive agricultural land of the plain and the extensive moorish wet ground of Rhoshirwaun which, in antiquity, was used for grazing and fuel but not much else.

At the south-western limit of the Llŷn peninsula there are single and dispersed hut circles on the higher rocky ground of Mynydd Anelog, Mynydd Mawr, Mynydd Bychestyn and Pen y Cil which fringe the agricultural plateau of Uwchmynydd. The lack of evidence across the farmlands of Aberdaron is undoubtedly a consequence of extensive arable agriculture over centuries.

The earliest evidence of religious experience in the Llŷn landscape must be sought in the monuments of the Neolithic period and Early Bronze Age. There are around fifteen standing stones in the study area. There is a cluster near the banks of the river Erch, two stones, 180 m apart at Pen Prys, Llannor and a dispersed distribution extending to the south-western tip of the peninsula. It is impossible to determine the function of these stones. Some may be outliers or signposts to more extensive complexes of ritual activity, no longer visible. Others may be associated with burial. Most are an evocative expression of historical depth in the landscape. There are no certain stone circles or circular embanked ‘henge monuments’ in the area, although it has been suggested that a circular ditched enclosure, discovered from the air as a cropmark and confirmed by geophysical survey, at Cwmistir between Edern and Tudweiliog, might be an early prehistoric ritual enclosure.

The earliest Christian churches on the Llŷn peninsula are very difficult to identify and difficult to interpret, as is the case with many aspects of the Early Middle Ages, in the absence of direct evidence. The character of early churches and their organisation may, in many cases, be described as quasi-monastic or ‘clas’ churches. They were not yet part of a parochial system but were operated on community lines. The clas (a later term) describes a very wide range and type of church from the important and influential communities of Aberdaron and Clynnog Fawr and its offshoots within Llŷn, to small churches run by a local community with no other influence or interest outside its township boundaries. As an example, a clas church could come into existence if the freeholding head of a kindred, with the consent of its heirs and the sanction of the king or lord, transferred its rights in the land of the community to the benefit of a church, by making it and maintaining it. The customary rents and dues owed to the king or lord would then be transferred to the maintenance of the church. One of the community would have to be a priest and the head of the family, cleric or not, would be styled ‘Abbot’. Another scenario might involve the king or lord granting land for the construction and maintenance of a church and, perhaps, the installation of a younger member of the family or relative to hold that church. In either case, the church, and its community, would be freed from royal taxes. Certain appurtenances and rights accrued. The community, the claswyr (the ‘monks’), had a vested and inheritable interest in the landed endowments of the church, the abadaeth. An area of sanctuary (the noddfa) extended from the church and provided protection for those who required it. In one documented instance, in 1114, Gruffydd ap Rhys ap Twedwr of Deheubarth, pursued by Gruffudd ap Cynan’s men, took sanctuary in the church of Aberdaron. Gruffudd’s men were sent to drag him out but Aberdaron stood firm and ‘did not allow the sanctuary of the church to be violated’ (Brut y Tywysogion, Peniarth MS, 20 sa.1112).

Two important sixth-century memorial stones, found at Anelog, near Aberdaron, bear inscriptions which identify ‘Senacus, the priest, who lies here with a multitude of his brethren’; and ‘Veracius, the priest, here he lies’. The inscriptions use Roman capitals with serifs, ligatures and contraction marks in the style of grave markers to be found in many towns of the late Roman Western Provinces, indicating, at least, a familiarity with certain aspects of contemporary continental Christianity.

The early churches of Llŷn were almost certainly of wooden construction. The earliest surviving structural evidence of the use of stone is of the twelfth century. Aberdaron, with its twelfth-century Romanesque arched door, in three orders, is the best example, albeit much added-to and altered over the centuries. Those churches where a clas association can be identified have significant potential for there to have been an earlier church in that location.

During the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries there was a movement of reform which considered the old clas churches to be in decay and outmoded in respect of the continental orders which were making headway across England and Wales. Many of the clas communities were encouraged or persuaded to relinquish their rights in the abadaeth in favour of communities of Augustinian canons. Augustinians were chosen because the flexibility of their rule allowed them to undertake parochial responsibilities, as did the priests among the claswyr. Other clas communities seemed almost to melt away, leaving the church in the hand of a rector within a diocesan structure. In practice, concessions were made both to the claswyr and to the new occupants of the church. Again, Aberdaron provides the clearest example on Llŷn. The claswyr of Aberdaron retained their personal and property rights, their bond tenants were enfranchised and additional royal land on the mainland was granted by Dafydd ap Gruffydd, Lord of Cymymaen.

A second and important example refers to a grant of the church of Nefyn by Cadwaladr ap Gruffudd ap Cynan, in the 1170s or thereabout, to the Augustinian abbey of Haughmond. There are certain indications which suggest that the church was originally a clas church, raising the possibility that the establishment of Nefyn as a commotal maerdref had not occurred before the grant to Haughmond.

Between the twelfth and early sixteenth centuries stone-built churches became a very significant and visual component of the medieval landscape. There were considerations of a tenurial nature to take account of too. The township of Llannnor with its five dispersed hamlets was in the tenure of St. Beuno, that is to say, Clynnog Fawr. Carnguwch had also come within the orbit of Clynnog.

The Bishop of Bangor’s interests across Gwynedd were extensive. In the cantref of Llŷn the Bishop maintained a manor house and demesne lands at Edern. He was also landlord of the townships of Llaniestyn, Abererch, Llangwnnadl, Penrhos, Llanbedrog and Edern itself.

Surviving twelfth century detail is clearly visible at Aberdaron and also at Pistyll. The earliest visible masonry at Llannor is of the thirteenth century, which encompasses the entire unicameral structure before the addition of a fifteenth-century tower and modern porch and chapel. In its time it must have been the largest church in Llŷn. Llangian also has thirteenth-century work at the west end with a very clear distinction between that phase and a fifteenth-century extension. Similarly, Llaniestyn has surviving thirteenth-century masonry at the west end which was extended eastward in the late thirteenth century.

Perhaps the most expansive phase, however, centred on the year 1500. Llaniestyn, Llanengan, Abererch and Aberdaron churches all built new aisles adjacent to the previously extended structures and introduced arcades of four-centred arches between for communication. Llangwnnadl, on a much earlier structure, built two additional aisles, north and south of the early nave in the 1520s and 1530s punctuated the walls with three, four-centred, arches.

The style in these late fifteenth- and early sixteenth-century churches is predominantly perpendicular, with the exception of Llaniestyn which retains a version of an earlier, triple-lancet window, style at both east gables. At this same period, similar styles of roofing were employed using collar-beam, arch-braced, trusses, sometimes strengthened with wind-braces and raking struts. Good examples, some repaired or restored, may be seen at Llangian, Llanengan, Pistyll and Llangwnnadl.

Llandudwen Church

Llandudwen is an interesting sixteenth- and seventeenth-century rebuild on medieval foundations, incorporating square stone-mullioned windows with ovolo moulding.

Fourteen of the twenty-eight parish churches in the study area have either been demolished and left as ruins or rebuilt on the same site during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The church at Deneio, close to the assumed llys of the maerdref of Afloegion has been reduced to a stable ruin of low walls.

A new church was built on a new site in the centre of Pwllheli in the nineteenth century and it was rebuilt again in 1887. St Peter ad Vincula at Meyllteyrn was rebuilt on the same site but it, too, is now a ruin. Many of the nineteenth-century churches which have replaced earlier ones are solid Victorian conceptions of diverse medieval themes as, for example, at Edern and Tudweiliog. Two unusual churches in this category are the rusticated Romanesque church built to replace the St. Hywyn’s original Romanesque at Aberdaron and St. Gwninin’s church at Llandygwnning.

The rise of religious Non-Conformism in the later eighteenth-century was fuelled by eloquence and enthusiasm. Among those evangelists who fired up the mass rallies was John Elias, a son of Abererch. The smaller meetings which followed these rallies, held within individual communities, required accommodation of some kind. Lofts and barns were let, or given freely for the purpose. As the movement and momentum increased within communities which had outgrown their rented rooms, steps were taken to acquire more spacious and suitable buildings. One of the earliest chapels to have been used,and which still survives, is Capel Newydd, Nanhoron. Capel Newydd is barn-like and may very well have been a barn before its use as a chapel. Acquiring land for a dissenters’ chapel was not always easy and the gentry were not always well disposed to Non-Conformists. However, the Puritan background of the Nanhoron family was a legacy which endured. Captain Timothy Edwards of Nanhoron was a benefactor and his wife, Catherine, joined the congregation after her husband’s death. Capel Newydd (Independent) stood close to the edge of common land, and, in 1782, a second chapel of Calvinistic Methodists was built within the common at Nant, a short distance away.

An Independent Chapel was built at Tudweiliog in the late 1820s a short distance down the lane to Brynodol and not far from the parish church. The style here is also very like a barn or agricultural building and has a house for the minister, adjacent and in-line.

During the second quarter of the nineteenth century Non-Conformist chapels were built more spaciously to accommodate larger congregations. In a small village like Aberdaron there were three chapels, Independent, Calvinistic Methodist and Wesleyan before 1890. Chapels, by this period, were designed and the designs which found favour were predominantly classical. Victorian Gothic designs were less popular but do occur. Capel Nebo, at Rhiw, for example, rebuilt in 1876 has a restrained, but nevertheless Gothic facade as does Capel Peniel at Ceidio, immediately adjacent to the restored church there. Those churches with classical elements in their design present recurring motifs, with some variation, and a generally standard arrangement of openings, at least until the end of the century when chapels grew larger still and the designs more adventurous. Common elements of the second half of the nineteenth century include large half-round arches springing from abaci upon tall pilasters occupying a good portion of the gable façade. The arch frames two tall windows with rounded heads, above which are set a kind of pseudo-hood mould. Two paired doors with rounded heads stand outside the frame on either side of the facade. This arrangement and others recur several times and are probably the work of local architects. The round arched theme described above is replicated precisely, for example at Capel Berea, Efail Newydd, in 1872, Bethania at Pistyll in 1875, Bryn Mawr in 1877 and Salem, Sarn Meyllteyrn 1879.

The Church in Llangwnnadl is dedicated to Gwynhoedl, who was one of the earliest Saints of Lleyn, being senior to St. Beuno, who founded Clynnog Fawr and Pistyll, and junior to St. Deiniol, who founded Bangor Fawr and the Cathedral Church of the Diocese. The tombstone which was erected to mark his burial place (in Llannor) was kept until recently in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford and bears the name the “Vendestle Stone.”This stone is now back in Llyn due to the endevours of Cyfeillion Llyn and can be seen at Plas Glyn y Weddw in Llanbedrog.

However, in the Church there is another stone connected with Gwynhoedl which is also reputed to be his tombstone. It was discovered during the renovations of 1940, when the plaster was removed off the walls. It can be seen in the south wall of the Church, and on it is cut a Celtic Cross (ring cross). No doubt that the cross was originally painted, as traces of red colouring are still visible; this stone has been dated by eminent historians around the year 600 A.D.

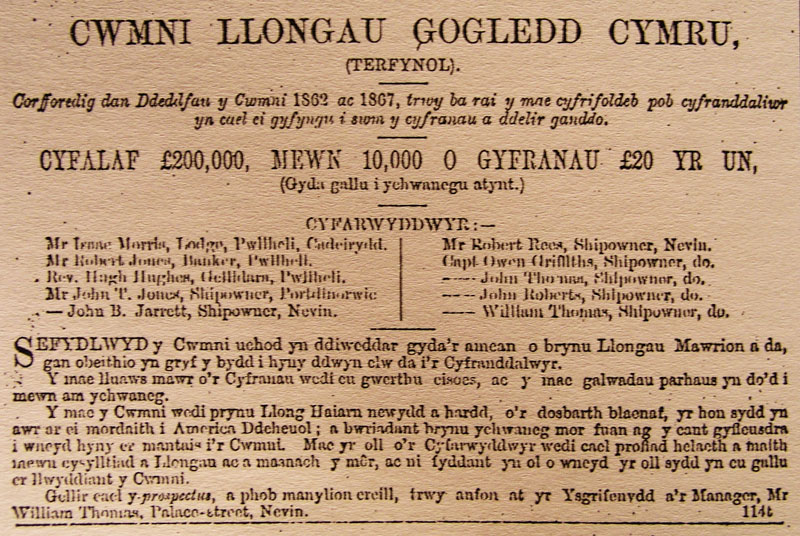

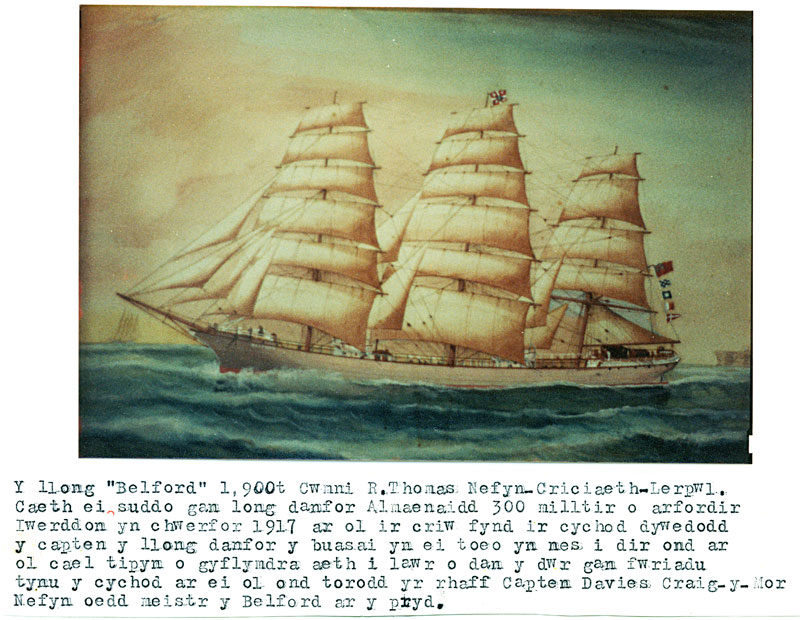

A hundred years ago the small ports of Gwynedd were crammed with working sailing ships, hundreds of them owned and bullt locally, engaged both in coastal and oceanic trades. In villages like Moelfre.and Newborough, Nefyn and Criccieth, almost every cottage bred generations of seamen. Amlwch and Porthmadog, Barmouth and Pwllheli and the slate ports of the Menai Straits, Porth Penrhyn, Port Dinorwic and Caernarfon, all had much in common with similar maritime communities in Scandinavia and North America.

The beautiful three masted schooners which came from the shipyards of Porthmadog, known to contemporaries as the Western Ocean Yachts, gained an enviable reputation in the slate trade to the Elbe ports and Scandinavia, in the salt fish trade of Newfoundland and Labrador as well as carrying phosphate rock, timber and general cargoes which took them to ports from South America, the Carribean, the Mediterranean, the Gulf of Finland.

Similarly the fine iron barquentines and schooners of Amlwch were known from Rio Grande do Sul and Porto Alegre to Hamburg and Twrku Peloras to Fredrickstad. At Holyhead it was the vital ferry to Ireland which created the demand for ships and seamen, and the heroic stories of the Tara and Scotia in two world wars are but examples out of the wealth of material in the story of this once busy port.

The Stuart at Porth Tŷ Mawr 1901

The largest vessel to come from local shipyards was the wood barque Ordovic, 875 t, at Port Dinorwic in 1878, but many large wooden sailing ships built in the Canadian Maritimes and the United States were owned and managed in Gwynedd in the last century. And this is only a brief glimpse of a maritime heritage extending from the days of the early Celtic saints and the vikings, the castles of Edward I strategically placed to make the most of the seapower, and the days of pirates and smugglers on a coast which has more than its share of tragic wrecks’ and outstanding rescues by brave lifeboat crews.

MV HELVETIA ran aground at Porthsgaden 31-10-1911 and sunk whilst under tow 11-11-1911.

Mynydd Rhiw In the 1950s shallow quarry hollows along the ridge of Mynydd Rhiw, towards the north end, were identified as the product of extraction of fine-grained baked shale rock used in the production of tools, particularly axes, during the Neolithic period. Further investigation in 2005 and 2006 defined a more extensive area of exploitation for a length of 400m. Radiocarbon determinations suggested that this activity was on-going during the fourth and third millennia BC. This process of extraction and manufacture could claim to be described as the earliest industrial activity in Llŷn.

Penrhyn Du The presence of lead on the Penrhyn Du headland has been known since at least the early eighteenth century. Lewis Morris charted the waters of Ceiriad and St. Tudwal’s roads between 1737 and 1748. He marked the position of the lead mine and recorded the name of an inlet, adjacent, Porth y Plwm – the Lead Harbour. He further recorded that there were veins of lead and copper at Penrhyn Du. The lead mine had formerly worked to good profit, but ‘now lies under water, … recoverable with proper engines’.

The attempt was apparently made to drain the water using a Boulton and Watt steam engine but ‘the expenses proved superior to the profits’ (Pennant, 1773, ed. John Rhys 1883, 368).

At Hen Dy, Tyddyn Talgoch, a tenement on the Penrhyn Du headland, a surveyor of the Vaynol Estate commented in 1800 that ‘the lands have suffered very much by the Mine Company of Penrhyn Du who sank several shafts in it and left them open, and the heaps of rubbish delved therefrom not trimmed or levelled’. Hyde Hall, in 1810, observed that mines had been operational some years ago but had not been cost effective and had not been resumed. In 1839 a field in Hen Dy still retained a memory of the earlier works as Cae Hen Chwimse (chwimse = whimsy, a machine for raising water from the mine).

During the second half of the nineteenth century the lead mines were in operation again. A Cornish engine and engine house was installed in the 1860s and by the 1880s, 240 miners, dressers, washers and engine drivers were at work in the mines across the headland from Llanengan to Penrhyn Du. Many of these workmen had come to Penrhyn Du from other regions. Half of the mining population came from Cornwall and Devon.

Mynydd Rhiw and Penarfynydd Manganese was discovered at Mynydd Rhiw in the 1820s. Prospecting led to an expansion of the operations into Nant at Penarfynydd and Benallt below Clip y Gylfinhir. During the nineteenth and early twentieth century activity and production was intermittent. However, manganese was a strengthening agent in steel and was much in demand during two world wars. In the early years of mining, donkeys took the manganese to the shore at Porth Cadlan. During the later phase of greatest demand an aerial ropeway carried the ore above the village to the shore at Porth Neigwl. Inclines were used at Nant.

Nant tramway leading to lower level

Granite quarries between Trefor and Nefyn Igneous intrusions which define the visual character of the landscape between Trefor and Nefyn run in a chain of peaks and hard rock outcrops from Yr Eifl to Garn Boduan.

During the second half of the nineteenth century quarries were established where granite was accesible. Some of these quarries were small, others were much larger. A quarry was opened at Gwylwyr, north of Nefyn, in 1835; at Moel Tŷ Gwyn, Pistyll, around the middle of the century; Carreg y Llam, Porth y Nant in 1860 and Yr Eifl at Trefor in 1880. Together these and local quarries came together to form the Welsh Granite Company. The main business in the early years was sett making, to surface the roads of towns and cities. By the end of the nineteenth century the demand for setts had evaporated and the quarries which remained in business turned to crushed stone, as a component of tar macadam or as an aggregate for concrete. The quarries worked the seaward faces in bonciau, banks or horizontal ledges. There were ten or more bonciau at Trefor and six at Porth y Nant. Inclined tramways took the product to the shore for transportation. There was an intimate relationship between the quarries and the villages of Trefor, Llithfaen and, on a smaller scale, Pistyll. One hundred houses in a tight nucleation of terraced rows stood near the quarry workshops at the foot of the incline at Trefor. Llithfaen had been an agricultural settlement of four farms with a handful of encroachments onto the common in the early years of the nineteenth century. By 1890 there were 90 houses, mostly associated with the quarry of Nant Gwrtheyrn. Nant also had its own barracks, shop and bake house on site until its closure in the 1950s.

Mynydd Tirycwmwd Exploitation of the hard granite began in the second half of the nineteenth century, on the headland, at three locations, Gwaith Trwyn and Gwaith Ganol (Headland and Middle Workings) and a smaller quarry on the south side. Initially, boats would be beached on the shore, loaded and floated out at high tide, a procedure replaced by jetties. The main product during the nineteenth century was the manufacture of setts. The quarries closed in 1949.